Table of Contents

ToggleParenting doesn’t come with a manual, and even the most loving parents can unintentionally do things that quietly harm a child’s emotional and psychological growth. These patterns often stem from how we were parented ourselves, not from a lack of love, but from a lack of awareness and skill.

In this article, I want to help you explore three common yet deeply impactful parenting behaviours that can affect a child’s developing brain, emotional regulation, and self-worth, and what you can begin doing differently.

Whether you are a parent, educator, or practitioner, this is an invitation to reflect with compassion, rather than judgment.

1. Emotional Dismissal: When Feelings Are Minimized or Ignored

How it shows up in daily life:

You may be familiar with phrases like;

- “You’re fine, stop crying.”

- “That’s not a big deal.”

- “Don’t be scared; there’s nothing to be afraid of.”

- “Don’t be angry, you’re such a good child.”

- “You don’t have to feel that; think positive thoughts, and you will be fine.”

These phrases might sound like reassurance, but to a child, they send a powerful neurological message:

“My feelings are not safe to express.”

“My feelings are not real.”

“There is something wrong with me if I feel my feelings.”

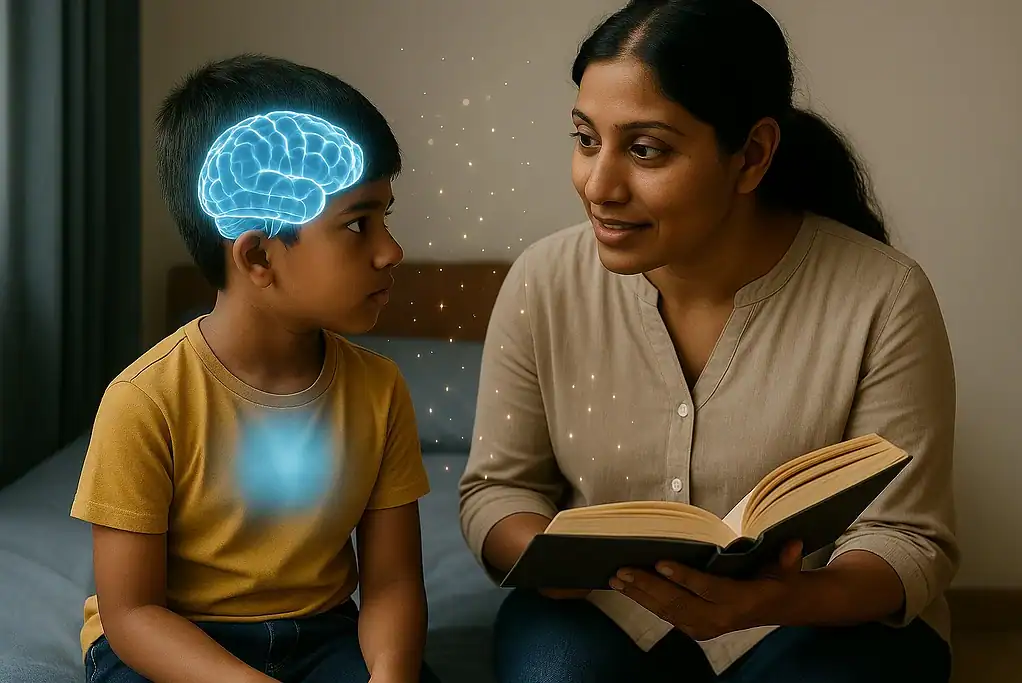

Children’s emotional brains (particularly the limbic system) are highly active and immature in early years. They rely on caregivers to help them make sense of their emotions. When adults dismiss or minimize their emotions, it interrupts a process called co-regulation, the external calming that gradually teaches the child how to self-regulate.

Without that safe attunement, a child’s nervous system remains in a heightened state of stress. Over time, this shapes the architecture of the developing brain, particularly the connections between the amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex, areas crucial for emotion regulation, memory, and reasoning.

The developmental impact:

- The child learns to suppress or disconnect from feelings. Instead of expressing sadness, fear, or frustration, they might go numb or erupt explosively.

- Emotional invalidation undermines the formation of self-trust. The child begins to doubt their inner experiences, “If my parent says it’s not a big deal, maybe what I feel is wrong.” This weakens self-identity and confidence.

- They may struggle to read or respond appropriately to others’ emotions. Either they overreact to emotional cues or avoid emotions entirely, making social relationships confusing and unstable.

- Chronic emotional dismissal keeps the stress response activated, increasing cortisol levels and shaping a brain that is wired for hypervigilance rather than calm reflection. This makes emotional regulation more difficult, even in adulthood.

What can we do differently:

Validate their experience. Validation doesn’t mean indulging every emotion; it means naming and acknowledging what’s real for the child.

“I can see you’re scared. That’s okay. I’m right here with you.”

This simple act calms the amygdala, lowers cortisol, and builds neural pathways of emotional safety.

2. Comparing Children to Others: The Silent Killer of Self-Worth

How it shows up in daily life:

You may be familiar with phrases like;

- “Look at how neatly your cousin keeps her things.”

- “Your friend always listens, why can’t you?”

- “Other kids can do this better than you.”

- “Why can’t you be more like your brother?”

- “When I was at your age, I had nothing, and you have everything, and you are wasting it all away.”

Comparison is often used as motivation, but it actually triggers shame, not growth.

From a developmental lens, identity and self-worth form through mirroring, how children see themselves reflected in their caregivers’ eyes, tone of voice, facial expression, and behaviours.

When a parent compares, the child learns, “Love and approval are earned, not given.”

This confuses their emerging sense of self. Instead of developing intrinsic motivation (“I’m proud of who I am”), they internalize conditional worth (“I’m only good when I’m better than someone else”).

The brain’s reward system, which fuels motivation and learning, begins to associate validation with external praise and comparison, rather than genuine curiosity or effort. Over time, this leads to an unstable sense of self-worth and constant performance anxiety.

The developmental impact:

- The child may feel constant pressure, fear of failure, and hidden resentment toward both the parent and the person they’re compared to. They learn to measure love by achievement rather than connection.

- Repeated comparison creates deep-seated inadequacy and perfectionism. Many adults raised this way may experience feeling not good enough, no matter what they achieve.

- Growing up with constant comparisons can lead to persistent feelings of jealousy. These children might become overly competitive, struggling to celebrate others’ success, or they may withdraw completely to avoid judgment. Friendships can feel threatening rather than supportive.

What can we do differently:

Instead of comparing, focus on the child’s individual growth and effort.

“I saw how much you practiced; that shows real perseverance. How do you feel about it?”

When praise centers on process rather than comparison, dopamine reinforces internal satisfaction, not external competition. That’s how intrinsic motivation and secure identity grow.

3. Not Repairing After Rupture: The Missed Opportunity for Connection

Every parent loses patience at times, raises their voice, walks away, or shuts down. The rupture itself isn’t the problem; it’s the absence of repair that causes long-term damage.

Children are exquisitely sensitive to disconnection. When a rupture happens, and the parent doesn’t come back to reconnect, the child’s nervous system interprets it as abandonment.

From an attachment theory perspective, repair teaches a child that relationships can survive conflict. This forms the foundation of secure attachment and emotional resilience. Without it, the child develops an emotional blueprint that says, “Love disappears when I make mistakes.”

When repair doesn’t happen after conflict, the body stays stuck in stress mode, either tense and alert (fight or flight) or shut down and numb (freeze). Over time, this stress affects the nervous system, making it harder to manage emotions, sleep well, digest properly, or stay healthy.

The developmental impact:

- The child experiences guilt, shame, and confusion after conflict, without understanding what went wrong. Over time, they may learn to suppress emotions to prevent future disconnection.

- They may internalize blame for every rupture: “It’s my fault when people are upset.” This creates adults who over-apologize, fear confrontation, and struggle to voice needs in relationships.

- They either cling to others out of fear of abandonment or withdraw to avoid potential rejection. Relationships become either too close or too distant, rarely balanced.

- Without repair, the brain’s mirror neuron system, which supports empathy and relational understanding, weakens. The child’s nervous system becomes less adaptive in regulating stress through connection, leading to chronic anxiety or emotional numbness.

What can we do differently:

Repair doesn’t require perfection; it requires humility and reconnection.

“I shouldn’t have yelled. I was overwhelmed, but that wasn’t fair to you. I love you, and we can start again.”

This simple act teaches the child that love can coexist with imperfection, wiring their brain for emotional safety, empathy, and secure connection.

The Bigger Picture: Why These Behaviours Matter

Emotional dismissal, comparison, and lack of repair all disrupt one fundamental developmental process, the wiring of emotional safety in the brain.

A child’s brain grows through relationships. Every interaction, whether calm or chaotic, shapes neural pathways that influence how they think, feel, and relate for the rest of their lives.

When a parent’s tone, gaze, and presence communicate safety and attunement, the brain integrates emotion, logic, and connection. When interactions communicate threat, shame, or disconnection, the brain wires for protection instead of connection.

The good news is that the brain is plastic; it can change. Every act of awareness, validation, and repair helps rewire those old pathways, building new circuits of trust, empathy, and resilience, for both the child and the parent.

Final Reflection

Parenting and guiding children isn’t about perfection; it’s about presence, curiosity, and repair. If you see yourself in any of these patterns, you’re not alone. You’re human.

Awareness is powerful. Each time you choose to pause, listen, and reconnect, you’re not just shaping your child’s development; you’re reshaping your own. And that’s how generational healing begins.

Thank you for reading and for your heartfelt support and interest. As always, your thoughts, insights, and stories are warmly welcome.

With grace and gratitude,

Lux Hettiyadura

Directress, Child/Adolescent Development & Parenting Coach Education – Ignite Global

If This Resonated With You…

🌱Join my free monthly Attachment Healing Circle, a safe, supportive space to heal your attachment system through secure, nurturing connections. Join here.

🎥 Keep Learning – Watch related videos on my YouTube channel where I break down attachment science into everyday language and share tools you can use right away. Watch here.

📚Read More- If you’d like to explore this topic further, I invite you to read my earlier article, How Parental Mental and Emotional Health Shapes Child and Adolescent Development. Read here.

💌 Join the Conversation – Subscribe to my newsletter, Strings Attached, to receive regular insights, stories, and resources on attachment, relationships, and healing.

🤝 Share the Love – If this article touched you, share it with someone who may need these words today. Sometimes, the smallest act of passing on knowledge can create the biggest ripple in someone’s healing journey.

🌿 Stay Connected – Healing is not meant to be done alone. By staying connected, you’re creating a community of awareness, compassion, and growth.

References

Ainsworth, M.D.S., Blehar, M.C., Waters, E. & Wall, S. (1978) Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Allen, J.G. (2013) Mentalizing in the Development and Treatment of Attachment Trauma. London: Karnac Books.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979) The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Cozolino, L. (2013) The Social Neuroscience of Education: Optimizing Attachment and Learning in the Classroom. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Cozolino, L. (2017) The Neuroscience of Human Relationships: Attachment and the Developing Social Brain (2nd ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Eisenberg, N., Spinrad, T.L. & Eggum, N.D. (2010) ‘Emotion-related self-regulation and its relation to children’s maladjustment’, Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6, pp. 495–525.

https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131208

Feldman, R. (2017) ‘The neurobiology of human attachments’, Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 21(2), pp. 80–99.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2016.11.007

Fonagy, P. & Target, M. (2002) Early Intervention and the Development of Self-Regulation. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 22(3), pp. 307–335.

Gunnar, M.R. & Quevedo, K. (2007) ‘The neurobiology of stress and development’, Annual Review of Psychology, 58, pp. 145–173.

https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085605

National Scientific Council on the Developing Child (2010) Persistent Fear and Anxiety Can Affect Young Children’s Learning and Development: Working Paper No. 9. Harvard University Center on the Developing Child.

Available at: https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/persistent-fear-and-anxiety-can-affect-young-childrens-learning-and-development/

Porges, S.W. (2011) The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-Regulation. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Schore, A.N. (2012) The Science of the Art of Psychotherapy. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Siegel, D.J. (2012) The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Siegel, D.J. & Bryson, T.P. (2012) The Whole-Brain Child: 12 Revolutionary Strategies to Nurture Your Child’s Developing Mind. New York: Bantam.

Thompson, R.A. (2014) ‘Stress and child development’, The Future of Children, 24(1), pp. 41–59.

Tronick, E.Z. (2007) The Neurobehavioral and Social-Emotional Development of Infants and Children. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Van der Kolk, B.A. (2014) The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. New York: Viking.