Table of Contents

ToggleLearning is not just something that happens in classrooms. It begins the moment a baby opens their eyes and seeks connection. It continues through every relationship, every interaction, and every experience that activates the developing brain.

Modern neuroscience, attachment theory, and developmental psychology all point to one truth:

Children learn best when they feel safe, connected, and emotionally supported.

This article explores how learning occurs in the brain, the impact of attachment relationships on a child’s academic and emotional development, and how early experiences shape the individual we become in adulthood.

What Is Learning? A Neuroscience Perspective

Learning is the lifelong process through which we gain new knowledge, skills, behaviors, and ways of understanding the world. It changes how we think, feel, respond, and solve problems. Each time we learn, whether through experience, practice, reflection, or guidance, we strengthen and refine the neural pathways that shape how we move through life.

At the center of this process is neuroplasticity: the brain’s remarkable ability to reorganize and form new connections. Neuroplasticity allows us to adapt, grow, remember, and recover. The brain is not fixed; it continuously rewires itself in response to experiences, relationships, emotions, and environments. This is what makes learning possible at any age.

But here’s something most people don’t realize:

The brain cannot learn efficiently when it does not feel safe.

When a child is stressed, frightened, shamed, or overwhelmed, the brain activates its survival system (fight, flight, or freeze). In this state:

- The amygdala becomes hyperactive

- The prefrontal cortex, responsible for focus, reasoning, and decision-making, shuts down

- The hippocampus struggles to form memories

This means a child may want to learn, but their brain cannot process information effectively.

Learning requires:

- emotional safety

- curiosity

- regulation

- connection

- play

These are biological conditions, not luxuries.

Why Attachment Is the Foundation of Learning

Attachment is the emotional bond between a child and their caregiver. It is not just a psychological concept; it is a neurobiological regulatory system that shapes how the developing brain grows and learns.

A securely attached child experiences consistent emotional presence and attunement. In simple terms, the caregiver communicates:

“I am here. You matter. Your feelings make sense. You are safe with me.”

When a child feels this level of emotional safety, their brain shifts into an optimal state for learning:

- Stress hormones decrease

- The nervous system stays regulated

- Attention and memory improve

- Curiosity and exploration increase

- Confidence strengthens

Imagine a toddler at the playground. She climbs a ladder, looks back at her mother, receives a warm smile or a wave, and continues climbing. That simple exchange captures the entire learning cycle:

Connection → Safety → Exploration → Learning → Mastery → Return to Connection

This is the essence of a secure base, a caregiver who provides a dependable emotional anchor. When children know they can return to comfort and reassurance, they feel safe enough to explore, take risks, develop independence, and build resilience.

While parents are usually a child’s primary secure base, educators, coaches, mentors, and other caregivers often become secondary attachment figures. Their presence is especially important for children who have experienced inconsistent caregiving, stress, or adversity. When these adults understand trauma and attachment, they can offer vital co-regulation and emotional safety, allowing the child’s brain to settle, focus, and engage with learning more effectively.

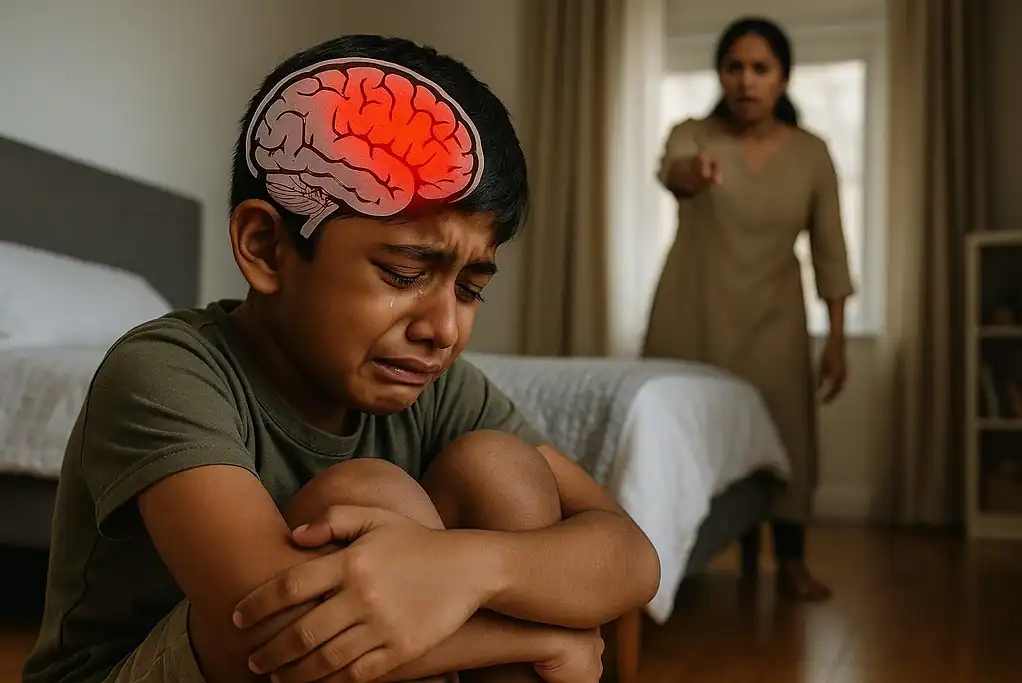

How Insecure Attachment Disrupts Learning

Children with insecure or inconsistent attachment often struggle with learning, not because they lack intelligence, but because their nervous system is chronically activated. When children do not feel emotionally safe or supported, the brain shifts into a self-protective mode dominated by the amygdala, the brain’s threat-detection center.

When the amygdala senses emotional uncertainty, whether through inconsistency, criticism, withdrawal, or unpredictability, it becomes hyperactivated. This sets off a chain reaction in the nervous system:

- Stress hormones (cortisol, adrenaline) increase

- The body prepares for fight, flight, or freeze

- And most importantly, blood flow is redirected away from the learning centers of the brain

During heightened threat states, the brain prioritizes survival over cognition. This means less oxygen and glucose reach the prefrontal cortex (responsible for focus, reasoning, problem-solving) and the hippocampus (responsible for memory and learning).

As a result, children in insecure attachment systems may appear inattentive, unmotivated, disruptive, overly perfectionistic, or emotionally reactive, when in reality, their brain is overwhelmed, not misbehaving.

How Different Insecure Attachment Styles Influence Learning

Anxious Attachment

The child becomes hyper-focused on relational cues:

“Am I good enough? Are you upset? Will you leave? Am I safe?”

This constant internal monitoring keeps the amygdala activated, fragmenting attention and reducing cognitive capacity. The child may develop:

- Perfectionism

- Fear of failure

- Difficulty focusing

- Dependency on reassurance

Their brain are working hard to manage emotional uncertainty, leaving fewer resources for learning.

Avoidant Attachment

The child suppresses needs to stay emotionally safe:

“I’ll handle it myself. I can’t rely on adults.”

This protective strategy keeps the prefrontal cortex overly engaged in self-regulation and emotional suppression, often at the cost of help-seeking, collaboration, and flexible thinking. They may:

- Appear independent but struggle to ask for help

- Avoid challenging tasks

- Disconnect emotionally

- Show reduced creativity or risk-taking

Their learning looks “flat”, not because they don’t care, but because caring feels unsafe.

Disorganized Attachment

For this child, the caregiver is both a source of comfort and fear. This results in chaotic amygdala activation and unpredictable stress responses.

They may struggle with:

- Emotional dysregulation

- Concentration difficulties

- Inconsistent behavior

- Confusion or overwhelm

- Significant learning challenges

This is not misbehavior. It is the brain adapting to survive emotionally unsafe environments.

The Brain Structures Most Affected by Attachment & Stress in Learning

Insecure attachment and chronic stress impact the entire learning network:

- Prefrontal Cortex

Reduced blood flow impairs planning, focus, and impulse control.

- Hippocampus

Stress hormones disrupt memory formation and recall.

- Amygdala

Becomes overactive, scanning for threats instead of allowing learning.

- Cerebellum

Reduced coordination and slower pattern learning.

- Basal Ganglia

Difficulty forming routines or consistent mastery.

- Anterior Cingulate Cortex

Weaker attention regulation and emotional monitoring.

- Vagus Nerve & Brainstem

Chronic dysregulation disrupts calm, presence, and mind–body integration.

A child raised in stress develops a brain wired for protection. A child raised in connection develops a brain wired for exploration. This distinction, the difference between a brain surviving and a brain learning, defines the trajectory of a child’s academic, emotional, and relational life.

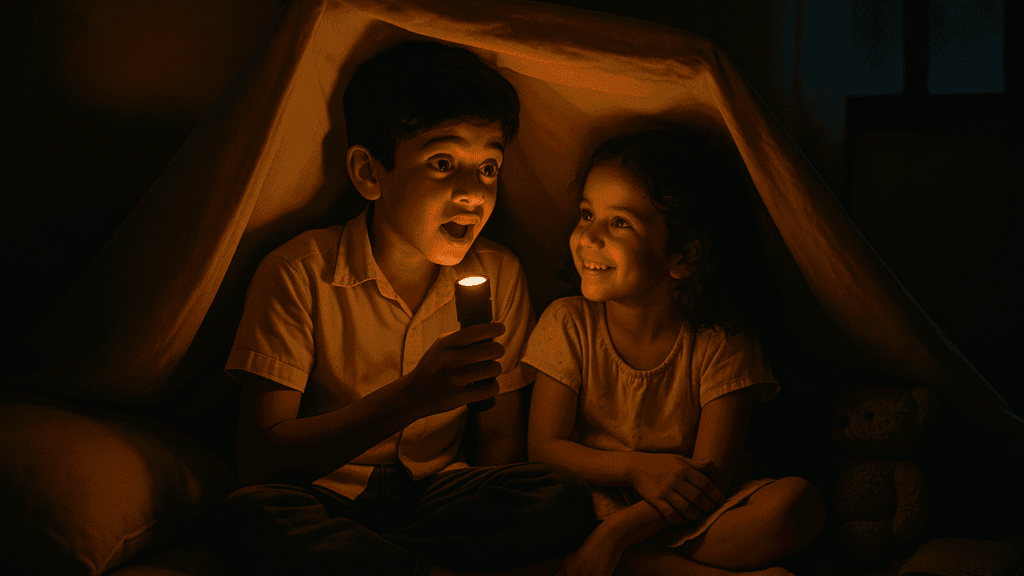

Play and Creativity: The Biological Engines of Learning

Play is not a break from learning; play is learning. It is the most natural, efficient, and biologically necessary way a child’s brain develops. During play, several key learning systems switch on simultaneously:

- Dopamine increases, boosting motivation and curiosity

- The prefrontal cortex strengthens, supporting attention, planning, and emotional control

- Children take risks, experiment, and make sense of the world

- Imagination expands

- Social and communication skills evolve

- Emotional regulation improves

A child pretending to be a doctor is practicing empathy and perspective-taking. A child building with blocks is learning physics, sequencing, balance, and spatial reasoning. A child drawing a story is developing narrative thinking, creativity, and emotional expression.

With every playful moment, the brain forms millions of new neural connections. Without play, development becomes restricted, emotionally, cognitively, socially, and even neurologically.

Creativity: A Sign of a Safe, Open, and Regulated Brain

Creativity is not limited to art, design, or talent. It is a neurobiological state where ideas flow freely, problem-solving is flexible, and the mind feels spacious enough to explore.

Children express creativity most easily when:

- Mistakes are safe to make

- Their efforts are welcomed rather than compared

- Exploration is encouraged

- They feel emotionally supported

In emotionally unsafe or critical environments, the opposite occurs. Children may become:

- Self-doubting

- Risk-avoidant

- Overly perfectionistic

- Disconnected from curiosity and imagination

Creativity requires psychological spaciousness, and spaciousness requires safety. When a child feels secure in their relationships and their environment, the brain quiets its threat response, allowing the imagination, prefrontal cortex, and problem-solving networks to fully activate.

How Early Childhood Shapes Adulthood

Every adult carries traces of their early experiences into their relationships, work, learning patterns, emotional responses, and sense of self. Childhood does not simply “pass”; it becomes the foundation upon which the adult nervous system, personality, and inner world are built.

When children grow up in emotionally safe, attuned environments, their developing brain receives consistent cues of security. This shapes adulthood in profoundly positive ways. Adults raised with emotional safety often demonstrate:

- Secure and healthy relationships

- Resilience under stress

- Confidence in their abilities

- Openness and curiosity toward learning

- Emotional intelligence and empathy

- Creativity and flexible thinking

- Healthy boundaries

- The capacity to trust and be trusted

These qualities emerge from a nervous system that learned early on:

“The world is safe. I can explore. I am supported.”

The Impact of Early Stress or Inconsistent Care

When childhood is marked by unpredictability, criticism, emotional distance, or chronic stress, the developing brain adapts for protection rather than growth. These adaptations are not signs of weakness; they are survival strategies.

Adults shaped by early relational stress may face:

- Low self-worth

- Chronic self-doubt

- Difficulty asking for help

- Fear of failure or rejection

- People-pleasing or emotional avoidance

- Perfectionism

- Instability in relationships

- Creative blockages

- Learning anxiety or shame

These characteristics are not fixed traits or personal shortcomings; they are neurobiological adaptations, protective strategies the brain developed in response to emotional unpredictability. Importantly, contemporary neuroscience shows that through neuroplasticity, these patterns remain modifiable throughout life.

The Adult Brain: Healing, Rewiring, and Re-Learning

The adult brain remains remarkably adaptable throughout life. With the right conditions of safety, attunement, and support, neural pathways can reorganize and outdated survival patterns can transform into healthier, more secure ways of being.

This means adults can:

- Heal attachment wounds

- Relearn emotional regulation

- Rebuild creativity and curiosity

- Form secure and fulfilling relationships

- Develop new learning patterns and habits

Coaching, therapy, supportive relationships, psychedelic-assisted therapeutic practices, mindfulness, somatic practices, and compassionate environments all help the brain shift from protection to expansion.

We are not defined by our childhood. We are shaped by it, but never confined by it. Our capacity to grow, heal, and learn remains alive in every stage of life.

Why This Matters for Parents, Educators, and Coaches

When adults understand the neuroscience of learning, the way we interpret children’s behavior transforms. Instead of asking why a child is not listening, why they seem distracted, or why they are struggling academically, we begin to ask more meaningful questions:

- What does this child’s nervous system need to feel safe?

- How can I serve as a secure base for them?

- What conditions will support their brain to engage, focus, and thrive?

A regulated adult helps regulate a child. A regulated child becomes an open, curious, capable learner.

Learning Grows in the Soil of Safety

Children learn not simply because we instruct them, but because their brains feel safe enough to explore. Attachment offers the foundation of safety, play provides the practice, creativity expands the mind, and relationships weave all of these elements together.

When we nurture a child’s emotional world, we strengthen their cognitive world. When we create environments of safety and connection, we unlock their innate potential to learn, grow, and flourish. And when we integrate the neuroscience behind these processes, we help shape healthier, more resilient generations.

Thank you for reading and for your heartfelt support and interest. As always, your thoughts, insights, and stories are warmly welcome.

If you’d like to deepen your understanding of the Neuroscience of Attachment and Learning, I warmly invite you to join my complimentary masterclass. Together, we will explore how attachment patterns and emotional safety shape the developing brain. You can register using the link below.

With grace and gratitude,

Lux Hettiyadura

Directress, Child/Adolescent Development & Parenting Coach Education – Ignite Global

If This Resonated With You…

🌱Join my free monthly Attachment Healing Circle, a safe, supportive space to heal your attachment system through secure, nurturing connections. Join here.

🌱Join my free monthly Global Parenting & Child Development Support Network, a safe, supportive space to learn about whole-child development, conscious parenting, and nurturing harmonious family systems. Join here.

🎥 Keep Learning – Watch related videos on my YouTube channel where I break down attachment science into everyday language and share tools you can use right away. Watch here.

📚Read More- If you’d like to explore this topic further, I invite you to read my earlier article, Unintentional Parenting Behaviours That Silently Damage a Child’s Emotional, Social, and Psychological Development. Read here.

💌 Join the Conversation – Subscribe to my newsletter, Strings Attached, to receive regular insights, stories, and resources on attachment, relationships, and healing.

🤝 Share the Love – If this article touched you, share it with someone who may need these words today. Sometimes, the smallest act of passing on knowledge can create the biggest ripple in someone’s healing journey.

🌿 Stay Connected – Healing is not meant to be done alone. By staying connected, you’re creating a community of awareness, compassion, and growth.

References

Ainsworth, M.D.S., Blehar, M.C., Waters, E. & Wall, S. (1978) Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Bowlby, J. (1969) Attachment and Loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. New York: Basic Books.

Bowlby, J. (1973) Attachment and Loss: Vol. 2. Separation: Anxiety and Anger. New York: Basic Books.

Bowlby, J. (1980) Attachment and Loss: Vol. 3. Loss: Sadness and Depression. New York: Basic Books.

Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University (2010) The Foundations of Lifelong Health Are Built in Early Childhood. Available at: https://developingchild.harvard.edu

(Accessed: [insert date]).

Feldman, R. (2017) ‘The neurobiology of human attachments’, Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 21(2), pp. 80–99.

Gunnar, M.R. & Quevedo, K. (2007) ‘The neurobiology of stress and development’, Annual Review of Psychology, 58, pp. 145–173.

Immordino-Yang, M.H. & Damasio, A. (2007) ‘We feel, therefore we learn: The relevance of affective and social neuroscience to education’, Mind, Brain, and Education, 1(1), pp. 3–10.

Kolb, B. & Gibb, R. (2011) ‘Brain plasticity and behaviour in the developing brain’, Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 20(4), pp. 265–276.

LeDoux, J. (2000) ‘Emotion circuits in the brain’, Annual Review of Neuroscience, 23, pp. 155–184.

Perry, B.D. & Szalavitz, M. (2006) The Boy Who Was Raised as a Dog: And Other Stories from a Child Psychiatrist’s Notebook. New York: Basic Books.

Porges, S.W. (2011) The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-Regulation. New York: W.W. Norton.

Schore, A.N. (2015) ‘Attachment theory and research: The first 50 years’, Attachment & Human Development, 17(6), pp. 681–706.

Siegel, D.J. (2012) The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press.

Siegel, D.J. & Bryson, T.P. (2011) The Whole-Brain Child. New York: Delacorte.

Sroufe, L.A., Egeland, B., Carlson, E. & Collins, W.A. (2005) The Development of the Person: The Minnesota Study of Risk and Adaptation From Birth to Adulthood. New York: Guilford Press.

Vygotsky, L.S. (1978) Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Gopnik, A., Meltzoff, A.N. & Kuhl, P.K. (1999) The Scientist in the Crib. New York: William Morrow.

Brown, S. (2009) Play: How It Shapes the Brain, Opens the Imagination, and Invigorates the Soul. New York: Avery.